Coral Reef Conservation Heroes Part 1 of 4: Dr. Rod Salm

October 7, 2020Coral reef conservation would not be what it is today if it weren’t for a multitude of passionate individuals devoting their lives to the future of this ecosystem. Over the coming weeks, we will be featuring interviews with four such people, all who have received the International Coral Reef Society’s Coral Reef Conservation Award.

Dr. Rod Salm was the inaugural winner in 2018, in recognition of his half-century’s experience developing innovative science and management strategies for tropical marine ecosystems. Now on a “forever sabbatical,” Rod previously worked for IUCN and The Nature Conservancy, and has trained and mentored conservation scientists from many countries, with a focus on understanding resilience in the face of global change.

(Photo by Sharon Winslow, 2015)

How did you become interested in coral reefs?

I saw my first coral as an 8 year old swimming along the Mozambique (Moçambique) coast. It was a cauliflower coral, Pocillopora verrucosa, and I can still picture it perfectly today. After starting the fishwatching program for the Lindblad Explorer in 1971, the first natural history tour ship, I saw truly pristine reefs that had never been dived previously. These blew me away and I was caught hook, line, and sinker.

First coral species Rod Salm saw, cauliflower coral, Pocillopora verrucosa. (Photo by FredD, 2014)

Your career has taken you across the world, from India to the Caribbean and in between, how would you describe the changes you’ve seen in the world’s coral reefs?

In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, I used to get frustrated by all the fish in the way of the scenic reef shots I was trying to capture. Nowadays and almost everywhere, it is getting harder to get photos with fish in them unless in a conservation area. While conservation efforts have impressively enabled the recovery of former fish stocks, including some iconic species, we aren’t seeing the size and numbers of pelagic species like dogtooth tuna that were regularly seen back in the day. And coral reefs near coastal developments are degraded and some even lost forever under a persistent thick blanket of silt. Coral bleaching and related mortality has taken out huge areas of coral reef or changed them altogether.

What was the biggest barrier you faced in getting folks to care about the plight of reefs?

The silvered surface of the sea was always the biggest barrier facing us when trying to generate interest in marine conservation generally, but especially for coral reefs. People could not see beneath the sea easily, despite the dogged efforts of iconic pioneers like Jacques Cousteau. He essentially put the underwater world in everyone’s living room. But when push came to shove and we needed to get things done, we needed a way to peel away the reflective surface of the sea so people could really see with their own eyes what was happening right where they were.

Consequently, there was a vague interest but largely indifference from people about the need for coral reef conservation. Today, the biggest barriers have moved from awareness and indifference to greater issues in the realm of global politics.

Near Ilha Quitangonha, Mozambique.

What do you see as the potential impact the Allen Coral Atlas can make for the world’s coral reefs?

The first step is to find out where reefs are and map them accurately. This provides the focus that reef assessments need to find targets and identify different features that need investigation. From nautical and topographic maps to aerial photographs and satellite imagery (and basically anything I can get my hands on), this is how I have used maps to help me plan a reef assessment, locate different reef zones and benthic communities for in-water verification. There is no adequate, accurate, and sufficiently detailed source of information available. Aerial photos where they exist and are available are expensive and the improved and freely available satellite imagery are great sources even if cover is limited in many remote areas. The Allen Coral Atlas merges satellite imagery with other layers in the attempt to provide the detail we need to make conservation decisions.

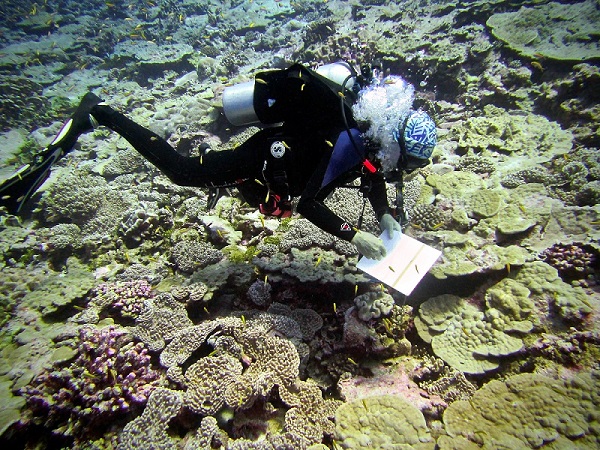

Rod collecting coral reef data on Palmyra atoll. (Photo by Sharon Winslow, 2016)

Rod inspecting Staghorn coral, Acropora muricata. (Photo by Stephanie Wear, 2010)

What makes you most excited about the potential of tech in protecting coral reefs?

Once the tech is sufficiently developed and the detailed layers in place, it has the potential to enable analysis at multiple scales. The double advantage of reliable large scale (regional) and fine scale (local) rapid coupled with inexpensive analysis of reef condition and conservation needs would be a terrific outcome. I understand that this is going to be a long and expensive goal to pursue. It’s important to continue pursuing a global map of reefs, but, at the same time, going deeper into countries or locations with good data and ease of access to refine the data layers for two reasons. The first is to demonstrate what really is achievable; and the second is to demonstrate to the world where the Atlas project is going in terms of its utility and applicability to world needs. Palau would be a great place to start.

Rod collecting coral reef data in Palau. (Photo by Paul Marshall, 2009)